| Arbitrage opportunities come and go - hedge funds will live to fight another day |

Back |

| New reports are emerging in the financial media every day about the poor performance of hedge funds, and the impact this will have on the long-term potential of the sector. Fiona Reddan reports from the annual Dublin Funds Industry Association (DFIA) conference, where speakers attempted to put the recent losses in perspective, and were bullish about the prospects of this sector, which is now valued at over $1 trillion. |

The outlook for the alternative investment market was top of the agenda at the Dublin Funds Industry Association Annual Global Funds Conference 2005, which was held in conjunction with US industry association, the National Investment Company Service Association, and took place on May 17th -19th.

With Dublin now firmly positioned as the leading European centre for servicing hedge funds, the future outlook for the global industry is of huge importance to Ireland’s international financial services sector.

Speakers at the ‘Alternative Investments – What Next?’ session, held on the afternoon of the 19th, focused on the recent poor performance of the sector, as well as future trends.

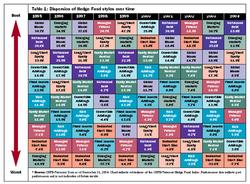

| | Table 1: Dispersion of Hedge Fund styles over time |

Fabio Savoldelli’s, managing director of Merrill Lynch Alternative Strategies, take on all the talk that ‘hedge funds are dead’ was the argument that arbitrage opportunities, on which hedge funds are based, come and go, pointing to the example that before technological innovations such as the internet, selling gold over the telephone from London to New York used to be an arbitrage opportunity.

To illustrate this point, Savoldelli presented the following chart (See table 1), which tracks the performance of the main hedge fund strategies over the past ten years. It is clear from the chart that opportunities do indeed come and go, and more often than not, come back again.

In 1995, global macro funds were returning over 30 per cent, and for the next three years continued to significantly outperform the market. However, by 1998, such funds had fallen by 3.6 per cent per annum, but were back on track again from 2000-2005.

Similarly, emerging market funds have had an uneven performance over the past 10 years, with a dismal year in 1995, when they fell by 16.9 per cent. The following year, emerging markets soared to the top of the league table, returning almost 35 per cent.

In 1998, emerging markets had a disastrous year, plummeting by 37.8 per cent, and leading to the infamous collapse of John Merriweather’s fund, Long Term Capital Management. However, these funds lived to fight another day and topped the table again in 2004, posting returns of 28.7 per cent. | | Table 2: Hedge funds - flashback to 1994 |

Going forward, Savoldelli told the audience that administrators will see a lot of trading in assets that previously hadn’t been seen, and other strategies will simply disappear.

Patrick Fauchier, senior partner and co-founder of Fauchier Partners, the specialist European firm dedicated

to the construction and management of customised portfolios of hedge funds, also downplayed the ‘death of hedge funds’. He said that in 1994 and 1998 it was also predicted that the hedge fund industry would collapse, so there is nothing new in commentators saying that the sector is in trouble, and that unless something dramatic happens at a major bank, the industry should continue as before. He believes that a correction was long over-due, and that now is a good to invest.

He also said that it is necessary to put the total hedge fund market in perspective, and remember that Fidelity Investments, one of the world’s largest asset a mangers, manages just 30 per cent less – at approximately $650 billion, than the entire hedge fund industry – at $1 trillion.

Another factor behind the poor performance, highlighted by Salvodelli, is the number of managers now active in the sector. With low barriers to entry, and ease of execution, there has been a surge in money going into the sector. However, Salvodelli maintains that there are too many managers, not all of whom are qualified to be hedge fund mangers, and they are dragging down the average return.

Fund of hedge funds

Fund of hedge funds (FoHFs), similar to long only fund of funds, but whereby investors invest in shares of hedge funds, are now growing faster than plain hedge funds.

Stephen Oxley, managing director of Pacific Alternative Asset Management Company Europe, an Institutional fund of hedge funds firm based in California which manages some $7 billion in multi-manager hedge fund portfolios, told delegates that in 2002, the top 10 hedge funds had combined assets of $71.5 billion, and by 2004 this had grown by 31.3 per cent to $93.9 billion. Funds of hedge funds on the other hand, had combined assets of $64.5 billion in 2002, and this grew by 150 per cent to $162.8 billion by 2004.

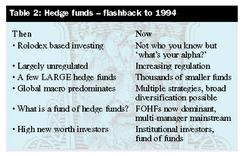

Institutions are mainly behind the growth in FoHFs, he said illustrated by Table 2. Oxley predicts that the huge growth which has characterised the industry to date will slow, but that FoHF will continue to dominate the market and get larger. By 2010, he predicts that institutional investors will account for 50 per cent or more of hedge fund assets, from their current base of around 20-30 per cent.

Retailisation

There were a number of divergent opinions on the issue of making hedge funds available to retail investors. Oxley argued that, in his opinion, hedge funds are simply not a retail product and therefore should not be made available to average investors. Fauchier and Salvodelli on the other hand, said that while not all types of strategies should be sold to retail investors, less complex strategies such as straight long/short funds should be sold to this market. |

|

| Article appeared in the May 2005 issue.

|

|