|

|

Wednesday, 11th February 2026 |

| Art market is no longer just for art lovers |

Back |

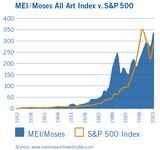

| Just as the property market has become a widely accepted investment class, the art market is now poised for a similar transformation, writes Bruce D. Taub. With the Mei/Moses index showing that the art market has held its own against the S&P 500, and outperformed the equities market in recent years, art is now a real alternative investment, and due to the non-correlation of price movement between art and other assets, the market offers significant opportunity to investors willing to do the research. But just as equity investors segment the market into ‘large-cap’ and ‘small-cap’ companies within a sector, it is equally important to segment within sectors of the art market, he adds. |

Georges Braque once remarked that the only valuable thing in art is ‘the thing you cannot explain’. As an avid collector, I recognise that the primary value of art should be considered in terms of the response it evokes in the viewer–emotional, personal, and impossible to quantify. | | Bruce D. Taub is the founder, chairman and chief executive of Fernwood Art Investments, LLC, a research and investment company focused on the art economy. |

But I also know that art is valued in explicit financial terms each time the ownership of a given work changes.

These values constitute a market which can be understood to the potential benefit of investors. As a professional investor, I am focused on finding investment opportunities that offer meaningful diversification benefits and significant outperformance potential, or ‘alpha’. The importance of both was reinforced by the recent volatility in the U.S. equities markets, when many investors learned a painful lesson in the necessity of diversification, and re-calibrated their investment performance expectations accordingly. It was during this period that I became convinced that fine art can offer sophisticated investors both diversification benefits (my art collection appreciated strongly in contrast to other holdings in my portfolio) and the potential for alpha (the art market being far less efficient than equities or bond markets).

Similar to real estate, art has always been an attractive investment for a select few. Individuals of wealth have acquired and traded objects of beauty since ancient times. Unlike real estate, widespread inefficiencies and barriers to entry remain in the art market, and have traditionally prevented more widespread diversification into art as an investment class. Just as the real estate market has become a widely accepted investment class, the art market–estimated by some to represent over $10 billion in annual sales in the United States alone–is now poised for a similar transformation.

New choices for sophisticated investors

The securitisation (perhaps a better term would be ‘democratization’) of previously illiquid investment categories is a steady, ongoing trend that has gained momentum with the spread of global capitalism, to the benefit of increasingly wider groups of investors. These benefits are typically enjoyed first by a small, privileged group of insiders, then by a wider group of sophisticated investors, and finally become retail investment opportunities available to all. | | Table 1: MEI/Moses AII Art Index v. S&P 500 |

Equities and bonds made this journey over the last century, and funds-of-funds are now making more non-traditional investment categories (such as hedge funds and private equity investing) accessible to individuals with smaller and smaller amounts of capital to invest. I believe that art is heading down the same road, to the eventual benefit of all investors.

How can the fine art market be understood in conventional investment terms? Several researchers and small private companies have recently begun to create art investment indices, employing analytic techniques to track the movements of the fine art market. Examples include indices created by Professors Mei and Moses of NYU, Art Market Research, Kusin & Company, and Gabrius. Though their creators use a variety of methodologies, these art indices all show that art’s performance and diversification benefits have been attractive over time. The index created by Professors Mei and Moses, for example, shows the art market holding its own against the S&P 500, and outperforming the equities market in recent years.

Even in times of weaker growth and less attractive capital market environments, the art market has risen significantly. This non-correlation of price movement between art and other assets can be employed as an effective risk management tool to achieve attractive diversification benefits within an investment portfolio. If the last few years have taught investors anything, it is the value of sophisticated diversification–particularly as global equity and fixed income markets become more correlated over time due to continuing economic integration.

The data now available also confirm that there is no such thing as a single, unified ‘art market’- a term as deceptively broad as lumping high yield corporate instruments and municipal bonds together under the category ‘bonds’ or the stocks of WalMart and Microsoft as ‘equities.’ | | Table 2: Performance of the Art Sector v. S&P 500 |

To be truly understood, the art market must be parsed into sectors, just as equity investments are categorised into technology and consumer sectors, for example.

Current data also show that performance and volatility vary substantially over shorter time periods and between different art market sub-sectors. For example, as Table 2 illustrates, the market for French Impressionists experienced a classic bubble in the late 1980s, fueled by enthusiastic Japanese art buyers. It has taken the better part of a decade for Impressionist prices to stabilise and, for the first three years of the 21st century, this sector of the art market has moved counter to the U.S. equities markets.

It is equally important to segment within sectors of the art market–just as equity investors identify ‘large-cap’ and ‘small-cap’ companies within a sector. For example, recent research by Mei/Moses shows that the lower-end paintings in their data set actually outperformed the general art market and the S&P 500 over several time periods.

It is one thing to analyse data, and quite another to put real money to work as an investment. Have serious investors ever ventured into the art market? Yes, and with impressive results. The best example of a large-scale investment in art by an institutional investor for the purposes of appreciation and portfolio diversification is the British Railways Pension Fund, which decided in 1974 to invest approximately ?40 million - 2.9 per cent of its overall portfolio across 10 collecting categories of fine and decorative art. The fund invested over a period of six years and then began to sell its collection in 1987. Through 1999, the compounded annual return of the British Railways art fund was 11.3 per cent.

Compared to the U.S. equities or real estate markets, the art market is highly inefficient– characterised by low liquidity, high transaction costs, low transparency, and highly differentiated products. It is far more attractive to try to outperform in this type of market than in a hyperefficient one, such as the U.S. equities market, where thousands of analysts and individual investors compete to find and act upon the smallest new insight about a public company before it is reflected in the share price.

Markets that require deep knowledge and skill have always intrigued me. In my experience, it is precisely these less-established corners of the investment landscape where the biggest rewards can be found. The least efficient markets offer the greatest opportunity for performance–provided that the investor has some kind of information advantage and/or ability to enhance value. The question then becomes, if broad art market and art sector indices indicate the potential for good performance, what additional gains might be achieved through active management?

Just like equities and real estate, fine art investments can be evaluated based upon a meaningful set of metrics. Rather than P/E ratios or net operating income, the value of a work of art is determined by factors such as provenance, condition, medium, subject matter, and size.

Just as the value of a company or piece of real estate can be enhanced, so too is the value of a work affected by the way it is owned. The active management of opportunity (systematically identifying undervalued works), value (curating works as a collection) and risk (diversifying exposure to the market), in addition to the well timed buying and selling of a work can create substantial value. Indeed, the world’s top collectors have always enhanced the value of the individual works they collect.

While the beauty and power of art will remain forever mysterious, the commercial benefits of art investment are becoming clearer by the day. The main barriers to more dramatic evolution in the art market are a lack of well conceived and executed investment vehicles and relevant systems to manage the underlying assets. A convergence of market developments–from the availability of market data to an increased investor appetite for non-traditional investments is steadily eroding this barrier. When it falls, sophisticated investors will participate in the benefits of investing in fine art. |

Bruce D. Taub is the founder, chairman and chief executive of Fernwood Art Investments, LLC, a research and investment company focused on the art economy.

|

| Article appeared in the April 2005 issue.

|

|

|